One of the biggest challenges of the 21st century is to make computers more similar to the human brain. We want them to speak, understand and solve problems — and now we want them to see and recognize images.

For a long time, our smartest computers were blind. Now, they can see.

This is a revolution made possible by deep learning.

Machine learning: The first step

Understanding machine learning is quite easy. The idea is to train algorithms on large databases to make them able to predict results from new data.

Here’s a simple example: We want to predict the age of a tree thanks to its diameter. This database contains only three kinds of data: input (x, tree diameter), output (y, tree age) and features (a, b: type of tree, forest location…). These data are linked by a linear function y = ax + b. With a training of this database, machine learning algorithms will be able to understand the correlation between x and y and define the accurate value of features. Once this training phase is completed, computers will be able to predict the right tree age (y) from any new diameter (x).

This is an overly simplistic description; it gets more complicated when we talk about image recognition.

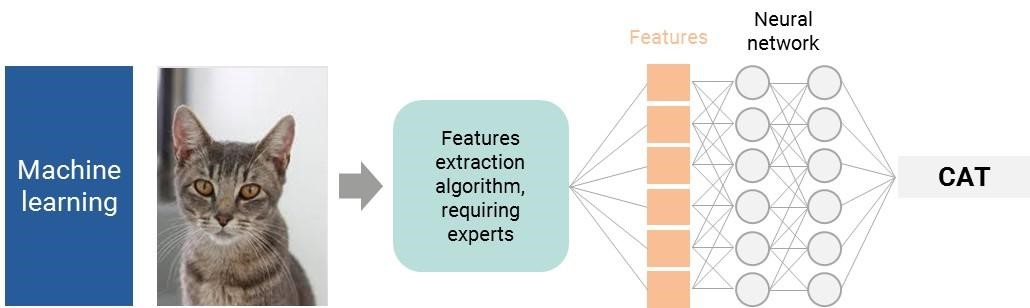

For a computer, a picture is millions of pixels — that’s a lot of data to process and too many inputs for an algorithm. Researchers had to find a shortcut. The first solution was to define intermediary characteristics.

Imagine you want computers to recognize a cat. First of all, a human has to define all the main features of a cat: a round head, two sharp hears, a muzzle… Once the key features are defined, a well-trained neural network algorithm will, with a sufficient level of accuracy, analyze them and determine if the picture is a cat.

What if we took a more complex item?

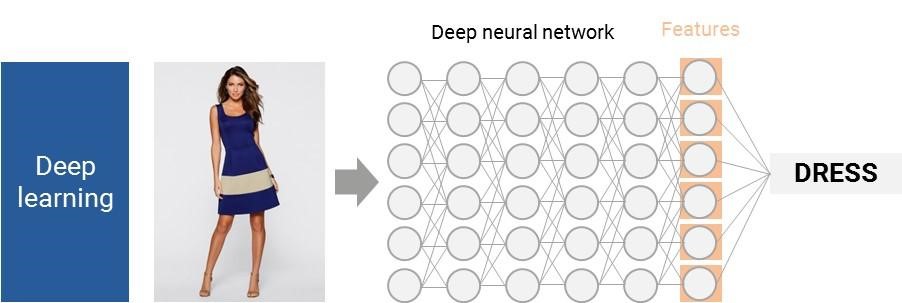

For example, how would you describe a dress to a computer?

You get the first limit of basic machine learning for image recognition: We’re often incapable of defining discriminating characteristics that would near a 100 percent recognition potential.

Deep learning: See and learn without human intervention

In the 2000s, Fei-Fei Li, director of Stanford’s AI Lab and Vision Lab, had a good intuition: How do children learn object names? How are they able to recognize a cat or a dress? Parents do not teach this by showing characteristics, but rather by naming the object/animal every time their child sees one. They train kids by visual examples. Why couldn’t we do the same for computers?

However, two issues remained: databases availability and computing power.

First, how can we get a large enough database to “teach computers how to see”? To tackle this issue, Li and her team launched the Image Net project in 2007. Collaborating with more than 50,000 people in 180 countries, they created the biggest image database in the world in 2009: 15 million named and classified images, covering 22,000 categories.

Computers can now train themselves on massive image databases to be able to identify key features, and without human intervention. Like a three-year-old child, computers see millions of named images and understand by themselves the main characteristics of each item. These complex feature-extraction algorithms use deep neural networks and require thousands of millions of nodes.

It is just the beginning for deep learning: We managed to make computers see as a three-year-old child, but, as Li said in a TED talk, “the real challenge is ahead: How can we help our computer to go from three to 13-year-old kid and far beyond?”

0 comments:

Post a Comment